Syndicalism: The Miners' Next Step

The unsatisfactory temporary nature of the settling of

disputes concerning wages and hours was a fertile soil for

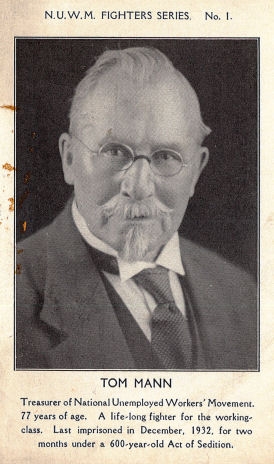

syndicalism, the 'gospel’ of industrial action. The main preacher

of this gospel in Britain was Tom Mann, one of the leaders of the

1889 'Dockers’ Strike. He advocated a free co-operation of the

workers, industry by industry, district by district, co-ordinated

and co-related with and to each other so effectively that would be

known exactly what output of commodities would be required and what

necessities of life would be required, and what the productive

capacity would be; in brief, the complete control of industry by

the working classes themselves. This change of society, Mann

argued, could not be brought about by the existing trade unions. As

in 1889, he pointed out that they were unable to act in a militant

fashion, because they had accepted the philosophy of

liberal-capitalism, and their organisation, based on the craft

divisions of industry, was not fitted for the struggle with the

capitalist owners. Economic or industrial organisations, bringing

about solidarity on the part of the workers, would prove to be

quite sufficient to bring about the entire economic and social

change desired, since the power of the capitalists - who function

‘as controllers of capital, as controllers of industry, as

controllers of the government, as controller of the

governmental machinery, as controllers of the fighting forces’ —

rested on the services, rendered by the working classes, a mere

refusal to render these services - a general strike - would bring

them down, and pave the way for the desired change of society. As

soon as the workers got hold of the economy - Mann: 'the social

situation is not only the vital one, but it is nineteen-twentieths

of the whole problem’ - the rest would follow. As a

consequence of this view Mann did not believe in the use of

political means and organisations.

The unsatisfactory temporary nature of the settling of

disputes concerning wages and hours was a fertile soil for

syndicalism, the 'gospel’ of industrial action. The main preacher

of this gospel in Britain was Tom Mann, one of the leaders of the

1889 'Dockers’ Strike. He advocated a free co-operation of the

workers, industry by industry, district by district, co-ordinated

and co-related with and to each other so effectively that would be

known exactly what output of commodities would be required and what

necessities of life would be required, and what the productive

capacity would be; in brief, the complete control of industry by

the working classes themselves. This change of society, Mann

argued, could not be brought about by the existing trade unions. As

in 1889, he pointed out that they were unable to act in a militant

fashion, because they had accepted the philosophy of

liberal-capitalism, and their organisation, based on the craft

divisions of industry, was not fitted for the struggle with the

capitalist owners. Economic or industrial organisations, bringing

about solidarity on the part of the workers, would prove to be

quite sufficient to bring about the entire economic and social

change desired, since the power of the capitalists - who function

‘as controllers of capital, as controllers of industry, as

controllers of the government, as controller of the

governmental machinery, as controllers of the fighting forces’ —

rested on the services, rendered by the working classes, a mere

refusal to render these services - a general strike - would bring

them down, and pave the way for the desired change of society. As

soon as the workers got hold of the economy - Mann: 'the social

situation is not only the vital one, but it is nineteen-twentieths

of the whole problem’ - the rest would follow. As a

consequence of this view Mann did not believe in the use of

political means and organisations.

Syndicalism had its supporters amongst groups of workers of

various trades. Most important of them, the South Wales miners. A

group of them, the Unofficial Reform Committee, embraced this

theory in a pamphlet, The Miners' Next Step that was issued

in 1912.  They advocated:

They advocated:

- A united industrial organisation, which, recognising the war of interest between workers and employers, is constructed on fighting lines, allowing for a rapid and simultaneous stoppage of wheel throughout the mining industry;

- A constitution giving free and rapid control "by the rank and file acting in such a way that conditions would be unified throughout the coal field; so that pressure at one point would automatically affect all others and thus readily command united action and resistance;

- A program of a wide and evolutionary working class character, admitting and encouraging sympathetic action with other sections of the workers;

- A policy which will compel the prompt and persistent use to the utmost ounce of strength, to ensure that the conditions of the workmen shall always be as good as it is possible for them to be under the then existing circumstances.

The main objective of a union, organised as proposed, should be industrial democracy. It would try to gain control of, and then to administer, the industry concerned. The co-ordination of all industries would take place on a Central Production Board, which, with a statistical department to ascertain the needs of the people, would issue its demands on the different departments of industry, leaving to the men themselves to determine under what conditions and how, the work should be done. "This would mean real democracy in real life, making for real manhood and womanhood. Any other form of democracy is a delusion and a snare”.

The Unofficial Reform Committee did not completely reject political action. This must, however, go on side by side with industrial action. Such measures as the Mines Bill, Workmen's Compensation Acts, proposals for nationalising the mines, etc. - they said - demanded the presence in Parliament of men who directly represented, and were amenable to, the wishes and instructions of the workmen. While, the eagerness of governments, to become a bludgeoning bully on behalf of the employers, could be somewhat restrained by the presence of men who were prepared to act in a courageous fashion,

The emphasis in syndicalist theory - and in The Miners’ Next Step - was on the production side of the economy; the consumption side was — to say the least — underdeveloped. This and other weaknesses were not as apparent in South Wales as they were elsewhere. There, in South Wales, though the coal-owners were powerful, they were numerically few, and the local middle class was - where it had developed at all - inevitably weak. Miners and their families completely predominated in whole areas. In parts of the South Wales coalfield, moreover, to propose a strategy for the miners was effectively to propose a strategy for the whole working class. It was a situation where it seemed that, but for the organisation of all workers in the mining industry into a democratic and revolutionary union, the mines could so easily be delivered to the miners and South Wales to its workers.